Hank Survived Caval Syndrome

Hank’s story began on May 10th, 2016. I’ll get to his story in a second, but I want to provide you a very brief, super-condensed description of Caval Syndrome.

Caval Syndrome - Heartworms On The Move

I’ll provide you links below so you can do your own reading on Caval Syndrome, but here is my layman’s understanding of this scary, life-threatening condition.

Bottom line – left untreated, Caval Syndrome will kill your dog. Fast.

Caval Syndrome occurs when, for reasons not fully understood, heartworms move against blood flow from the pulmonary artery (where they usually reside) and enter the heart’s right atrium, ventricle, and often, the vena cava. The worms tangle in the tricuspid valve and prevent its proper opening and closure, which severely interrupts normal blood flow. This event eventually (and quickly) leads to cardiovascular collapse.

Red blood cells, traveling through this mass of worms in the tricuspid valve are destroyed – ripped to shreds – this is called hemolysis. Dogs become anemic as the red blood cells are destroyed quicker than the body can make new cells. The remnants of the destroyed cells are shed in the urine. In every instance (4 cases) that I’ve known about or assisted with, every dog in Caval Syndrome peed dark-colored, reddish-brown urine.

Caval Syndrome also quickly impacts liver and kidney function, as seen on complete blood chemistry panels.

Dogs die quickly once Caval Syndrome occurs, sometimes in as little as 48 hours. It is a painful death.

It was thought that Caval Syndrome was related to moderate and large worm burden, meaning only dogs with a high worm load were at risk for Caval Syndrome. New studies suggest that disease progression is the cause: tissue changes, thickening, scarring, or other reasons for vascular resistance that sets up perfect conditions for worms to move into the heart. [1]

Hank - Clearly Sick But We Didn't Know It Was Caval Syndrome

The above picture is of Hank as he unloaded off the Animal Control truck, about to be checked in at a local, overcrowded shelter in southern Mississippi. If you didn’t know, Mississippi is the number one state in the country for heartworm – positive dogs. Recent statistics suggest that 1 in 10 dogs in Missisippi will test positive for heartworm.

You can see his discomfort, but you don’t know why. Look at his eyes; he is not well.

Lost in the busy-ness of shelter hustle and bustle

With Hank’s intake paperwork complete, staff place him in an indoor kennel so he can get settled for the night. It’s late in the day and he’d see the shelter veterinarian sometime the following day.

A volunteer with the shelter who is also a Boston terrier fan learned of Hank’s arrival and soon afterward went to his kennel to visit. She notified me of his arrival so Boston terrier rescue could make plans to accept him into rescue if needed.

[Advance notices help rescue organizations make plans! It takes time to find transport help, foster homes, and raise donations.]

I began to look for a standby foster home.

The volunteer called me again first thing the next morning: “Can you take him now?” I asked what’d changed and she let me know that she thought he had an infection. “He’s peeing blood,” she said. The shelter had already okayed his early release and the volunteer stated she was able to transport him the hour drive to our veterinarian right away.

I gave her the go.

Hank arrives to the vet

I was notified the moment Hank arrived at the veterinarian and for reasons I cannot explain, the vet saw him quickly. Most often, our dogs are dropped off and worked into the clinic’s patient schedule. Hank is alive today in a large part because he was evaluated so soon after arrival.

The vet called me with a report: “I believe Hank is in Caval Syndrome. He needs to go to the university vet school, NOW.”

Never a dull moment in rescue, I tell you! I was familiar with Caval Syndrome and I understood the situation. Changing my day’s plan, I quickly placed phone calls and texts to find an available person who could drop everything and drive Hank 3.5 hours to Mississippi State University.

I was in Atlanta, or I would have driven Hank myself.

I knew time was ticking and I knew how hard it would be to ask someone to make themselves available and drive a dog to the university. Most of my contacts had full-time jobs. I also knew Hank was actively and slowly dying, and I knew that the longer Hank went without emergency care, the less of a chance he had for survival. I was lucky to find someone as quickly as I did. Hank was lucky.

With Hank in the car moving toward Starkville, MS, I made another call – this one to the rescue’s president. I told her to put on her fundraising hat, we needed cash, fast! She and I experienced this emergency once before, with a dog named Bilbo. I also knew she could raise the several-thousand-dollar downpayment we’d need in 3 hours. She’s got skills.

The long ride to the university

By the time Hank settled into the pile of blankets on the front seat of Becky’s car, his condition was evident: he was not getting much oxygen. Not because he couldn’t breathe, but because his red blood cells were being ripped to shreds. With fewer red blood cells, oxygen couldn’t be transported throughout his body.

In defense, he became very still to reduce his body’s oxygen demand.

The transporter called me to check in, and I could hear the stress in her voice. “Is this dog going to die on me?” I gave her the only answer I had – “Maybe.” and I told her, “Drive. Drive safely, but drive.”

I prayed for smooth travel. Hwy 45 from South Alabama toward Meridian is well-traveled and known for traffic backups due to a variety of reasons. Any delay would contribute to Hank’s death.

I told Becky to continue to talk to Hank and also, when safe, place one of her hands on or near him in comfort. She wasn’t a reiki practitioner nor do I have a strong opinion about energy healing, but I do believe in hope. And Hank needed to know and feel that the human next to him was doing everything in her power to get Hank the help he needed. All he needed to do was hang on.

Later, Becky would share with me her observations of Hank during their road trip:

“He mostly laid in the seat next to me, but occasionally, he would raise himself up for a few minutes and then lay back down. You could tell he felt bad. A couple of times his breathing got fast and I got worried. Other times he was so still I checked his breathing.

“I kept talking to him and petting him and telling him to hang in there. Once he tried to wiggle closer to me but couldn’t get the energy. I drove the rest of the trip with my hand on him for comfort. I told him all about ABTR and that we would help him feel better and find him a wonderful home.”

Hank Riding With Becky to MSU

Hank had a team of veterinarians waiting for him at the door.

Arrival at Mississippi State College of Veterinary Medicine

A team of three veterinarians stood in the lobby as Becky brought Hank through the sliding glass doors of the emergency veterinary medicine lobby. We’d arrived after normal business hours. Two team members whisked Hank away to begin the assessment. The third remained and took a history report from Becky until she didn’t have the answers I did, so I, over the phone, filled in the missing information.

Hank was quiet and alert, but he was in bad shape; his legs were cold and his SPO2 (aka pulse oxygen) was low. A 5/6 heart murmur was noted. He was very anemic with a packed cell volume (PCV) or hematocrit of 17% – he required a transfusion. His respirations were quite high (66) as his body fought for oxygen. I don’t have his heart rate, but the discharge summary from MSU noted it was elevated. Hank also had substantial fluid build-up in his abdomen.

A diagnosis of Caval Syndrome was confirmed using a FAST scan – with this screening tool, the veterinarians could see a large presence of heartworms in Hank’s heart, specifically, the right atrium, tricuspid valve, and right ventricle. Surgery was the only option to save his life.

Using a special tool, the surgeon would remove or ‘harvest’ heartworms from Hank’s heart by entering the heart through the right jugular vein in the neck. Throughout the surgery, Hank would receive IV fluids, continuous blood transfusion, and an electrocardiogram machine was utilized to view the worms still remaining. The goal was to remove them all.

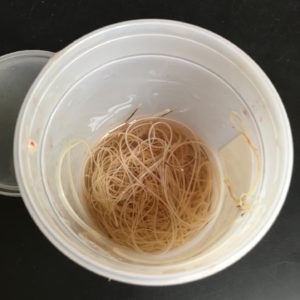

In the end, the skilled team with Mississippi State removed a total of 78 heartworms out of Hank’s tiny heart.

78 Heartworms from Hank's Heart

Post-Surgery: How long can you hold your breath?

With the heartworms removed from Hank’s heart, he still was in danger of dying. Heartworm doesn’t just affect the heart; they affect multiple organs and body chemistry all which had suffered greatly during this emergency. Hank was at great risk of complications post surgery. Could his body recover?

Hank’s medical records noted that he looked “brighter” the morning after surgery instead of the “quiet” disposition they’d recorded on intake. His appetite was good.

Roughly 10-12 hours after surgery, Hank’s SPO2 (pulse ox) remained low despite spending the night in an oxygen tent to help supplement his oxygen needs. While his heart murmur improved, now a 3/6, his respiratory rate and heart rate remained elevated – all signs he was working hard to get the oxygen he needed.

Hank was producing only a small amount of dark-colored, blood-stained urine.

Another complete blood chemistry test was performed. Hank continued to have low PCV, (now at 16%) and he had low platelets, as well. This meant his blood didn’t have good capability to form clots. Hank received another transfusion, this time a whole blood transfusion.

After this blood transfusion, his heart rate and respiratory rate began to trend toward normal. Hooray!

He remained on IV fluids and remained in his oxygen tent for the rest of the day and throughout that night. The staff began to feel more hopeful about Hank’s recovery.

Hank’s “donor dog” remained on standby in the event Hank required more blood transfusions.

Day 2 post-surgery

Roughly 36 hours after surgery, Hank went outside for his potty break, and for the first time since we’d met him, he peed normal-colored urine! Also, after coming in from his outside potty break, staff checked his SPO2 and it was at 100% saturation – excellent! His body was managing oxygen all on its own. The staff weaned Hank off of the oxygen tent and by the evening, Hank’s IV catheters were removed and he began taking his medications orally.

Another blood test was done, and the rest of his chemistry values were all within normal limits, including his kidney values. His Packed Cell Volume (PCV) remained mildly low, but he hadn’t needed a transfusion in some time.

Hank loved his caregivers and they all loved him!

Leaving MSU and further complications

Hank was hospitalized a total of 4 days at MSU, then discharged from the hospital to one of our regular foster homes. He required one more emergency hospital stay when his PCV once again plummeted and he needed another transfusion. I am so grateful for the foster parent’s watchful eye and her quick responsiveness in notifying the rescue of her concerns. I think we as fosters hesitate sometimes, thinking we are over-reacting or being a bother. If Hank’s foster had thought any of those things, I fear he might have had a dire outcome.

Long-term, Hank sustained damage to his tricuspid valve, pulmonic valve, and enlargement of his heart on the right side. He also had evidence of pulmonary hypotension. Some or all of this damage may be permanent. Thankfully, there are medications to manage these conditions.

Hank still had heartworm

Hank was immediately started on Doxycycline and Heartgard post surgery – the very next day, in fact!

Why? Well, he still had heartworm.

Not only did he have microfilaria (baby heartworm) circulating in his blood, but he likely had heartworm in another larval stage, migrating through tissue on the way to the heart. Doxycycline and Heartguard would safely rid Hank of the baby heartworm, and Hank would require a re-check in 2 months to see if any larval heartworm developed into adult heartworm. If so, Hank would need more heartworm treatment.

Hank giving his treatment team a high five!

Hank Is Adopted!

Hank’s surgeon fell in love with him and adopted him. He is an ambassador for heartworm prevention and quite the celebrity in our little rescue circle. He is certainly a miracle.

Another little tidbit for you: At the time Hank was treated for Caval Syndrome, he became the record holder at MSU for the highest number of heartworms ever harvested from a dog that survived. (A labrador retriever at MSU had over 150 worms harvested, but he did not survive post-surgery)

Standing on my soapbox for just a bit:

Hank is just one reason I am so, so, so outspoken about using best practices – the American Heartworm Society’s way – for diagnosing and treating heartworm.

If we’d gotten Hank before he was in Caval Syndrome, we could have, post verification of a positive heartworm test:

- evaluated his blood and urine to assess organ function and complete blood counts.

- reviewed radiographs for evidence of pulmonary changes and heart changes.

Those two additional diagnostics help your veterinarian stage the heartworm disease. You can’t learn the extent of heartworm damage in your dog with only a heartworm test. Even “high-positive” readout on a SNAP test will tell you limited information.

Knowing how your heartworm-positive dog looks on the inside, no matter the dog’s age, allows your treating veterinarian to tailor a treatment plan that fits what the complete diagnostics say, not just a snap test read-out.

Can Caval Syndrome be prevented? I don’t think so except to catch heartworm infection as early as possible or (obviously) keep heartworm infection from happening in the first place – things we have little control over in our rescue work. That said, I certainly want to know how heartworm infection has impacted a dog’s organs and chemistry. I want to know if my dog might be at advanced risk for Caval Syndrome. I want to be able to educate my foster home. I want to catch Caval Syndrome as quickly as possible. I can possibly save that dog’s life If I know and respond as early as possible.

Hank says it’s possible.

For More Information on Heartworm Prevention, Disease, and Treatment

For More Information on Caval Syndrome

Small Animal Cardiovascular Medicine – Caval Syndrome

AHS Heartworm Hotline: Understanding Development of Caval Syndrome (great explanation of current hypothesis on why Caval Syndrome occurs in a small number of heartworm positive dogs.) I’ve referenced this article [1]